David Ogden Stiers Explains the Secret of White Christmas' Success

About the author:

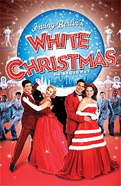

We’ll never forget David Ogden Stiers’ Emmy-nominated performance on M*A*S*H as Major Charles Winchester, a character who managed to be both imperious and loveable. Since that iconic series ended, Renaissance man Stiers has kept busy acting, conducting symphony orchestras (!), doing voiceovers and animation work and—over the past six years—playing General Henry Waverly in various productions of White Christmas. Luckily for Broadway audiences, Stiers is at the Marquis Theatre this holiday season, and we asked him to analyze the appeal of this holiday musical treat. Nor surprisingly, he wrote a warm and generous essay that gets right to the heart of White Christmas.

![]()

On the page it looked oh so simple. Play a military man (guy my age) who, after serving in World War II, runs an inn in Vermont. Military to Hospitality—no big jump; no songs; more importantly, no dancing (my bête noire).

What a simpleton I was/am. The ebulliently sharp mind of White Christmas director Walter Bobbie made me tremble and strive in the same breath. The deceptively “simple” dialogue of David Ives, asking every actor to just. say. it. Float it on the breeze; it doesn't need “explanation,” just energy and truth.

And the frosting on the fudge, a company of such talented actors/singers/dancers (you can juggle those attributes any way you want with each one of them; no one talent supercedes the others) and watching them rehearse was a refresher course in discipline, energy, willingness to try it again and the driving instinct to make us a company in the shortest possible amount of time.

That was six years ago, L.A. company of White Christmas. Since then, I've done St. Paul and Detroit companies, each of those iterations with my pal Ruth Williamson (a woman of incomparable heart, brass and sensitivity) who poohs my assertion that she taught me the role of Hank. (She taught me the role of Hank.)

This is sounding too detailed. I'll give the heart of the thing.

It's heart.

While some attendees find it glossy and goody-goody, older citizens remember exactly the America we are re-creating onstage: an America of genuine good-heartedness and compassion in which, should we have wronged someone, we apologized, were forgiven and then went to supper together.

Where the ability to accept a gift was as prized as the gift given.

When people went out of their way to “do” for one another because they could, and it was faster and made things run smoother for everybody. When there was a problem, no Dr. Phil: Candor and a forthright spirit cleared the air and sped the healing.

This season’s collection of White Christmas colts dazzles, as have all the other collections. The ensemble members are—to a person—among the most talented and breathtakingly energetic performers possible to assemble in New York. Technically sophisticated and capable of great goofiness backstage during warm-ups, they take my breath watching them stretch and banter and parody and exhibit concern for one another.

Example. One of the ensemble men got a fairly bad case of food poisoning, and while we were all concerned that his situation be righted as soon as medically possible, we watched as one of the swing performers made his terrified, tearful and ultimately joyous Broadway debut. We circled before the curtain that afternoon and blessed him. During the performance the backstage applause for his seamless precision in the variations in “Blue Skies” was thrilling to see and hear - and the smile on the face of that dancer at the end of “I Love a Piano” was unfiltered sunlight. Broadway was his that evening. And he became Broadway's.

It's a hive backstage; the storage, hallway and equipment square footage is not, um, generous. We're in each others faces, traffic patterns and costume changes nearly every second. And we make it work. Not making it work is not an option.

You may have gotten the impression that I love this gig. And I do. Not a back-breakingly long run; lustrous co-workers: James Clow (with whom I worked in the Detroit company; he's a pal and makes me laugh); the radiant and incisive Melissa Errico; Tony Yazbeck (the man who shames nightingales and whose dancing makes a plaything of gravity); and the compleat performer, Mara Davi. OK, and Cliff Bemis, who is a heart on legs; spirit of a 20-year-old in Ferdinand the Bull's body. Careful of him upstage of you. Hell, onstage. Madeleine Rose Yen, who plays granddaughter Susan. She is 28-year-old woman in a 10-year-old container. Genuinely sweet in a non-cloying way and very talented. But whatever is up with that three name thing?!

AND Denise AND Remy AND Leah…AND the wardrobe department AND hair AND the dressers (what a spectacular bunch of people). AND the crew backstage AND…this is quite particular and loving: Kelli Barclay. She is choreographer Randy Skinner's assistant. She knows e v e r y t h i n g. Every move each dancer makes—even dialogue within the choreography if it occurs. And is patient and soooo smart and funny and an entirely admirable person.

A personal (as though the foregoing wasn't) note. About musicians—artists in general, but in this particular instance, musicians. We are a blessed country. We have performing artists galore. When they really excel, they go to the urban centers and try to make it. Many of them work White Christmas to cover their holiday needs and income.

The orchestras in L.A., St. Paul and Detroit drew on the best studio musicians, orchestral personnel, academicians and soloists. The orchestra for White Christmas is, annually, a wonder. It is snow in Acapulco; palm trees in Novosibirsk. Energetic, subtle, sassy, assured and unflappable. Hats off to them all. And to Steven Freeman, their conductor, the most compassionate and inflexible leader one could conjure. For him I have to put on five hats to take off.

You know how during those award shows people who win get all cow-eyed about the feeling of family? Danged if it ain't true.